ANDREI MONASTYRSKI

EARTHWORKS –

("The Theme of the Peacock and the Condor

on the Expositional Sign Field of Moscow")

|

“ In my youth's years, she loved me, I am sure...” THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE OSTANKINO --- --- I TsZIN And she crossed her hands on her lap |

|

More often than not, traditional aesthetic discourse points from language to essence[2]. It is as if the critic were peering through some author's artwork at reality, nature, social relationships, or ideals, without forgetting to describe the specific constitution of the "lens" through which he is judging reality, accounting for the "observation deck" onto which his time has placed him.

Conceptualism was able to develop a specific conceptual discourse, since it combined criticism and artistic behavior in an unusual symbiosis. The boundaries of this discourse proved exceptionally permissive. (This is especially true for Soviet conceptualism; the Soviet conceptualists of the 1970s and early 1980s worked according to the principle of "necessity is the mother of invention", single-handedly writing examinations of their own work, since there was hardly any external criticism at all.) As a rule, these examinations also articulated some form of essence, but this essence always seemed elusive. The conceptual critic that constantly inquired from within the conceptual artist was unable to point toward essence as something conclusive, since the designated, reflected discursive point of what he actually meant to say in the first place immediately became a sign, and consequently, was no longer essence but an extension or contextual component of the conceptual artwork, constantly expanding. In the end, what happened was that the boundary between language (mediation) and essence became entropic, bleeding away into utter emptiness. In other words, essence became "essence"; placed into quotations marks, it became an everyday sign, an ordinary linguistic phenomenon, a point of reference from one could begin a discourse "in reverse", from "essence" back to language itself. Here, language is understood in purposeful perspective from above, complex – in comparison to "essence" – and "ontologized" through discursive replacement by a relational system; in this sense, it is much like a steel-concrete construction of a pedestal tier, while "essence" is much like the bottom of a pit, the ground upon which the entire superstructure of the discourse "in reverse" is to rest.

On the "return trajectory" of this discursive effort "upward" from "essence" to language, we might discover the Kantian pre-receptivity (or the Heideggerian "preunderstanding"), a notion that has tortured philosophy extensively. Now, however, pre-receptivity takes on a certain depth and is reworked in cultural terms in the form of a textual space, capable of giving rise to its own distinct objectivity[3] on the basis of its intrinsic problematique, which, in turn, is connected to the nature and varieties of its contexts. (In other words, it can now denote this pre-receptive gap and its depth as a meto- or pra-contextual space, transforming it into the object of examination through a conceptual critique.) In this way, we gain the possibility of examining to contextual objectivity or the ontology of the context, while traditional aesthetic criticism usually deals with instrumental contexts (i.e. social, historical, religious, art-historical, everyday contexts etc.). It is very important to note that this contextual objectivity became evident in the process of the conceptual discourse on its own accord, as a necessity: by "getting away" to somewhere unbelievably far away from the conceptual image in its interpretation, it was as if the conceptualist artist found himself in an airless, objectless space; having lost any sense of orientation (Kabakov, for an instance, has a piece called "There Are States When You Don't Know Right, Left, Up or Down"), the conceptualist artist could do little more than lean against the wall on which the image was hanging.

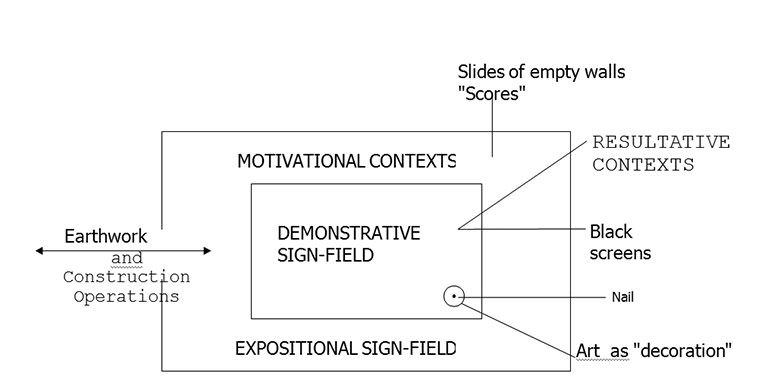

This is something that I experienced quite literally. When I put together the expositional sequence for the action "Score", which consisted of four black screens, I fastened them to the walls with long nails and wrapped these nails with white thread. It was then that I experienced the following aesthetic perception: the places at which these shields were nailed to the wall were, in fact, the entire expositional sequence's aesthetic points of bearing, points that concentrated the sequence's objectivity of images (and its content-plane): thus, it became clear that the point of affixment, the fastener – a purely technical moment, a technicism – had an aesthetic value for me. In "hanging on" the real wall in this way, I discovered its aesthetic tension and defined it as the expository sign-field, which adjoins (quite literally, through the nail) with the demonstrative sign-field, which consists of the material objectivity of the conceptual image and the textual objectivity of its interpretation (context).

Moreover, in my case of the black screens of "Score", its textual objectivity (context) turned out to be absolutely "opaque"": it is impossible to say anything about it at all, except that it defines itself as a demonstrational field with self-contained artistry as pure "decoration" (fastening nails wrapped up by white thread). But on the other hand, the expression of the demonstrational field as "demonstrativity" should be seen in light of "Score's" broader objectivity as an action, in combination with its slide-sequence. ("Score's" 30 slides depict both walls of the same room in which 4 black screens were hung to cover up the portions of wallpaper that the slides depict). Seen as such, this "demonstrativity" gave rise to a sign – composed of black screens and slides of the walls – that denotes the walls as an expositional sign-field. As such, it provided the possibility for introducing to conceptual discourse a notion that we can operate with in order to obtain concrete, varying articulations of the pre-receptive "gap's" textual space. In other words, the paradigms that present themselves through the introduction of this notion provide us with the possibility of developing a "pedestal tier" of our discursive efforts "upwards", from essence to language.

The first thing that becomes clear in examining the nature of the expository sign-field is that – unlike the demonstrative sign-field (images and their textual commentaries) – it does not belong to the artist but to the state, and that its objectivity practically knows no boundaries: apartment-walls and studios, museums, factories, institutions (both internal and exterior), the earth that is owned by collective farms (kolkhoz) and state-run farms (sovkhoz), roads, in short, everything, included water-resources and air-space belongs to the state. Only snow and fire are ownerless, or at least, there is no mention of these two elements as objects of government-property.

Going further, one can definitively say that everything located and everything that happens on this expository sign-field takes place in relation to the motivational contexts of artistic creativity. Moreover, the objectivity or ontology of these motivational contexts (like any form of objectivity) is not articulated through social, political, or any other kind of connections and relationships, but through concrete changes, through the building of roads, the digging of canals and foundations, the erection of buildings, the plowing of fields etc. Economic, social, and political connections and relationships are instrumental in relation to objectivity and its changes on the expository sign-field (the field of motivational contexts). The alteration of these connections and relationships articulates itself through different kinds of reconstructions[4] of expositional objectivity.

Since ours was the most ideologized of regions, these objective changes on the expository sign-field happened rather often, as we know (because here, this field manifested itself as tensely significant), and were cardinal in terms of quality. Moreover, they were not motivated by economic considerations, but by those of ideology. (For an example, churches were transformed into warehouses and then into museums etc.).

However, one could say with a great deal of certainty that any reconstruction's objectivity always took (and takes) place according one and the same law: first, a pit is dug to accommodate a building's foundation, then underground utilities and the edifice itself are built, and then new roads are paved (or old roads are mended). The objectivity of these earthworks and construction operations is inevitable to the course of any serious change on the expository sign-field. What is more, if one looks at these as semiotic changes, one might indeed wonder which cause-and-effect relationship they maintain with the changing structures of politics, economics, or other fields of culture. The question as to what came first remains open.

Usually, if the artist is engaged with his social environment, he is connected to the expository sign-field through the role of a "decorator": he either "decorates" with the help of some well-established tradition like landscape-painting or psychological portraiture (becoming practically "impervious" to the motivational contextuality of the expository sign-field), or he "reflects" any kind of reconstruction on this field (also through concrete objectivity, "decorating" or "criticizing" these reconstructions); in this case, he is "pervious" to the motivational context, although this "perviousness" is only permitted by official culture as long as he does not exceed the framework of his "decorative" function. (This includes "critical" work, whose "decoration" bears a dialectic-corrective character and is immediately defined as "beauty" or "deformity"[5]. "Deformity" is not allowed on the expository field and is either seen as hooliganism or a lack of talent.)

During the Soviet period, (underground) artists that were not engaged by society were left to their own devices and found themselves in a situation of utter freedom in relation to the expository sign-field that surrounded them. They were able to experiment ad libitum with the levels of "permeability" to the motivational context on their demonstrational field; they were able to "deform" at will in their basements and attic-studios; what is more, they were able to bring this "permeability" to an absolute level, which is what happened to Kabakov.

In the early 1970s (or even earlier on) Kabakov began to make paintings and albums whose images had a white, empty center. (The images themselves were located on the picture's periphery). The social motivation and mimesis of this type of image in Kabakov's demonstrative field as a field of a personal resultative context is understandable and was reflected by Kabakov himself more than once: don't you dare to enter the center; they'll crush you! This roughly amounts to the same motivation and mimesis that dictated Saltykov-Shchedrin's "A Modern Idyll". Yet this raises a question: where exactly did this particular objectivity or form of his works come from? Usually the artist will answer: "Through intuition, in an illumination" etc. In other words, (for the avantgardist) the sphere of morphogenesis, the motivation of objectivity is always sacral and rooted in notions such as talent, gift etc.

The rather broad, panoramic view of our discourse, and most importantly the genre of critical ideas and the non-committal nature of the conclusions postulated here allow us to discover (if we make allowances, of course) the motivation that supplies the "root-work" of this artist's objectivity. This motivation renders his demonstrative field absolutely transparent to the expository field; that is, it allows us to discover its "sacral" inspirator, in relation to which he (i.e. the artist) then structured his ontological (formal) mimesis.

This "sacral" inspirator (whose photograph will enter into the objective series of our discourse as the autonomous, conceptual piece of "Earth Works") can actually be found across from the "Russia House"[6], i.e. across from Kabakov's studio, on the corner of Sretensky Boulevard and Ulansky pereulok. It consists of a story of the construction of some kind of institute or office-building. This story of construction is rather unusual. According to Kabakov, this building, whose form is highly reminiscent of a sitting condor with his wings adroop, underwent construction for 20 years (from 1968 onward). It took 15 of these 20 years to dig the construction pit and to pour the fundament: the ground under the construction site turned out to be unstable; the buttresses caved into the ground; water accumulated in the construction pit; the iron frames turned rusty. In short, for fifteen years, an ugly hole in the ground gaped on the corner of Sretensky Boulevard and Ulansky Pereulok behind a fence, a hollow filled with rusty metallic girders, rods and water, a pit which Kabakov contemplated from the window of his studio as he illustrated children's books. The table at which he did this actually stood right next to the window from which you could see this place. While all the architects, engineers, foremen, and construction workers fussed around this pit, around the fundament's girder and cast-iron connection frames, Kabakov was working on his own frames and backdrops, on the albums "10 Characters", the painting "Berdyansk Spit" etc.; in other words, he was working pieces whose objective artistic quality took shape through frames and backgrounds: he developed an extremely complex system of frames, framings and backgrounds, which essentially were the actual objects that these works explored conceptually in terms of their aesthetic anatomy (i.e. beyond instrumental contexts). Around the same time, Kabakov began to transfer drawings from the albums onto large white panels; these included the three panels "Along the Edges" (with depictions of Hutsuls[7] and wagons).

In the end, toward the late 1970s, the fundament was finished and construction on the "condor" building across from Kabakov's studio finally began. At the same time, different kinds of plans and schedules began to appear on Kabakov's empty white panels, as if made some artist from the ZhEK.[8] In other words, when there was all that hustle and bustle around the construction pit on the expository sign field where Kabakov's "sacral inspirator" was located, Kabakov himself made pieces that were very existentially tense and directed "inward", deeper and deeper (or insider's language, "upward", "skyward") – remember his "Sky-1", "Sky-2", "Meon" – up, up and away to the point of the complete disappearance of words, images, and even the frames themselves, to an empty white space (as in the albums "10 Characters"). But when Kabakov's "inspirator" began to rise upward – as they began to build the institute itself – Kabakov began to make "foreign", "borrowed", or "external" works (in insider language, "lower pieces"); at first, these were simply grids with labels – "Sobakin", "Schedule for Taking Out the Garbage Can" – and later, when they started the finishing work on Kabakov's "inspirator", Kabakov started making colored panels, socialist realist ready-mades. I remember that when he had painted the first six panels of this series and I visited his studio for one of the last times, he told me, "Everything in my work has changed completely; it's completely extroverted and I can now do whatever I want".

In this way, one can actually discern a motivational connection to the point of complete mimesis between the construction work on Kabakov's inspirator (step-by-step changes in the objectivity on the expositional sign field) and the formal, structural changes on Kabakov's demonstrative sign field. In other words, one could say that the structural objectivity of a conceptual art-work's demonstrative field (in the case of its complete "transparency" for the motivational context of the expositional sign field) is mediated by the concrete objectivity of earthworks and construction works on the expositional field, through this or that "sacral" inspirator.

It is interesting that when they started to "cut out" Kirovsky Prospect, which could also be seen from the window of his studio, Kabakov was just beginning to work with his "ropes".[9] (The rope can be understood as a "road"; moreover, in our interpretational context, the garbage hung out on these ropes could be understood in analogy to the communal filth of the houses that they were tearing down during the construction of Kirovsky Prospect, while the labels on these pieces of garbage, including the piece "Box", could be read as the screams of those destroyed and useless things that were thrown out of these houses, or the screams of those who were throwing these things away).The story of how Kirovsky Prospect was constructed can also be seen as an inspirator for Kabakov and for the making of his genre of "ropes".

Interestingly, when the prospect was finished and the roof of the institute – which looked like the head of a condor – on the corner of Sretensky Boulevard and Ulansky pereulok had also been completed, Kabakov soon made his installation "Golden Underground River", which he himself sees as a piece that is cultural rather than full of existential tension.

Thus having made his demonstrative field absolutely transparent for the motivational context of the expositional sign field, Kabakov was able to achieve an unexpectedly powerful aesthetic effect on the level of formal structures: it was as if his works exuded those structural changes that were in fact taking place on the expositional (governmental) sign field. In this sense, Kabakov can be called a "state" artist, that is, an artist who reflects but does not decorate those structural, deep-level processes taking place on the expositional sign field, synergetic in terms of valence with relation to the economic and political events and motives. Moreover, we should note that the power of the signs on this valent field immeasurably exceed the power of the signs on the demonstrative field, since the expositional field's entire sign system is constructed and changes under the influence of the power of things, under the effect of life's necessities: its construction involves a huge number of people and organizations, down to the highest echelons of the government.

It is quite possible that it is the "governmental" character of Kabakov's works and their clear definition of the expositional context's motives determined the place and the success of his work in the West, namely the state-controlled museum. Around the same time, the place and success of the works of Komar and Melamid was located in private galleries (at least during the period that we are examining here), even if it would seem that the resultative contexts of their demonstrative field is far more vibrant and ostensive than the same type of context in the work of Kabakov.

In other words, one could such that the motivational context objectified in formal structures presents itself as "ontological" (or simply more "solid" or "deeper") in relation to the kind of resultative context that both art and spectator will usually handle.

The same motive of expositional objectivity (earthworks and construction work) can also easily be found in the history of "Collective Actions". Kabakov worked with the archetypes "house" and "road" (i.e. with Soviet urban communality). "Collective Actions", however, conducted its actions out in the countryside, on expositional sign fields that belonged to kolkhoz farms. As such, it worked with the archetypes "food" and "sustenance", and – through the interpretation of their actions (but not through their event-character!) – brought to light the expositional structures of the Soviet agrarian-industrial complex as an "empty action" (ineffective in a metaphorical sense and inane from the economic point of view).

(Aside from the agricultural exhibition near where Pantikov and I live, of course), the key "sacral" inspirator that gave form to the structure of our actions on the outskirts of town, digging pits etc. was yet another story of the prolonged and tortuous excavation of some kind of well of an unusual depth on a hill near the "Kosmos" movie theater, which I passed every day from 1976 to 1980 on my way to the trolley-bus stop in order to ride to work at the Literary Museum. There were earthworks in progress throughout all four of those years. And no-one really knew what exactly was going on.

In terms of scope – a sizeable number of construction wagons brought in around the excavation site; a high roof was put up over the pit; the pit itself was enclosed by a fence, and in the course of the work itself, which continued day and night, they used this amazing foreign equipment, mobile cranes and refrigerating aggregates etc. – the work in progress made the local inhabitants think that they were building another exit for the VDNKh Metro Station. But when I actually looked into the hole in the ground one day, I found that its diameter was no more than six meters wide, that its bottom was not visible (dozens of meters in depth), and that it obviously had absolutely nothing to do with the metro whatsoever. Later, it turned out that this was some kind of temporary sewerage well, through which they were installing new sewerage purification aggregates deep in the ground. These aggregates were meant to serve the entire area, ranging from Zvezdniy Boulevard, Ulitsa Koroleva, and all the way out to Ostankino. Actually, it's true: in those years, especially in springtime, there was a strong smell of shit in the air all around the "Kosmos" movie theater. What's interesting is that after the work was done (somewhere in the mid-1980s), no trace whatsoever remained of the well, not even a simple manhole.

It was during those years, when they were building this well, that we rode out of town to the field at Kievogorsk and carried through our action with the excavation of pits ("Comedy", "Third Variant", "Place of Action" etc.), and sometime in 1979, after "Place of Action", when they were finishing the construction of the new sanitary system and beginning to work on liquidating the well, I formulated my theory of the "empty action" as a non-demonstrative stage of the action's leakage into the demonstrative field. But in 1980, when the well had already been filled, I first introduced the concept of the "demonstrative field" and defined some of its zones in the foreword to the first volume of "Poezdki za gorod" [Trips into the Countryside]. (Of course, I did not see any connection between the hole they were digging and my own theorizing at that time.)

Our inspirator proved far more complex than Kabakov's inspirator. After all, it was devoid of any external appearance (its construction took place underground; the well was later filled up and disappeared without a trace, although it still stinks around the "Kosmos" movie theater, by the way, so that the whole fuss with the well also turned out to be an "empty action").

Deprived of the objective support of my inspirator (of course, all of this took place on a subconscious level), I began to "dig a hole" within myself in early 1981, and, having experienced a genre-crisis of the insider-aesthetics at the field at Kievogorsk (after the action "Ten Apparitions"), I turned to Russian Orthodox asceticism and, toward the end of 1981, I lost my mind. However, after about a year, I came to my senses and we resumed our actions, already placing a greater accent on factography and documentation rather than on the character of the event itself. (These actions include both the slide-film "Auditory Perspective of Trips to the Countryside" as well as all of the actions documented in the second volume of "Trips" as a whole).

After I lost my mind and was deprived of the unconscious though evident foothold of some kind of objective inspirator on the real expositional field, I began to make actions in "outer space". (This especially applies to the action "M" from the third volume, whose "heavenly quality" E. Bulatov underlined in his story "Zolotoi den'" (Golden Day). In other words, unlike Kabakov, who (unconsciously) always "relied upon" his inspirator (whose period of construction, by the way, was also drawing to a close), Collective Actions had practically no inspirator throughout this entire period. As a result, the motivational quality of our actions weakened considerably, so that we were largely concerned with factographic and auditory structure, i.e. with resultative contexts. During the initial period before my madness, when we worked on the ("governmental") motivational context under the influence of the "sacral" inspirator, using interpretation to reveal the system of agricultural industry as "empty action" (after all, our actions were carried out on a field owned by a kolkhoz and the government), our structures were just as "transparent" in relation to the expositional sign field; moreover, they were very tense in term of motivation. This was immediately felt in the West: it was this cycle of actions in the countryside that was published by Felix Ingold in the Swiss journal "Kunstnachrichten" (1980). This journal was academic, "museal", and "governmental", in a sense. Both the article's author and the journal's editor felt the governmental mimesis in these actions, i.e. they saw that these actions reflected the real state of affairs on the expositional sign field of the Soviet agricultural industry, even if direct reflections of this sort were absent in both our own interpretations and in Ingold's article. Instead, this aspect was highly mediated by autonomous aesthetic reflections, although its structures were quite obvious and spoke for themselves. Take, for an example, the action "Time of Action", in which a string of seven kilometers in length was unraveled across a kolkhoz-field over 1 ½ hours, with no apparent ending. Aside from its "Zen" content, this action had an obvious social-metaphorical meaning, which nobody understood, including its authors, since the expositional context was not taken into consideration at all. In other words, no-one thought about the fact that the action was taking place on the field of a Soviet kolkos, where many potatoes were planted although few of the potatoes harvested actually ever reached any of the shops, and if they did, then you knew all about their lack of quality.

In 1984, they tore up all of Kondratyuk Street (they were laying water-lines to the building that was under construction across the street from me), and I felt a new surge of strength and carried out the series of chamber-actions "Perspectives in the Space of Speech Space" together with Romashko and Sabine.[10] As I see now, the "sacral" inspirator of these actions were the earthworks that were taking place as the underground supply lines were being laid out to the building undergoing construction across the street from me. It is highly probable that it is because they were building an apartment house this time that the structures of apartment-based actions (rather than actions on the outskirts of town) entered my head. Incidentally, by this time I already felt some kind of connection between what was happening on the street in front of my window and what was happening in my head (ideas for actions), which is something I wrote about in the essay "Engineer Wasser and Engineer Licht". But still, all of this was still taking place on an unconscious level, even though this period marks the beginning of my work with a conscious schizophrenic syndromatique.

It was only after conducting the action "Score" and actualizing the problem of context in conceptual art (through the dialogue "TSO or Conceptualism's Black Holes", held with Joseph Backstein and published in the MANI anthology "Ding an Sich") that I was able to translate this syndrome into the realm of aesthetic autonomy. This translation gave rise to the conception of the expositional sign field as a field of motivational contexts, a conception that allowed me to look at the conceptual discourse's textual objectivity with a more generalized, distanced gaze. This gaze no longer unfolded through the context's instrumentality, but considered its ontology and gave birth to its own specific artistic qualities ("inspirators").

From a psychological (or psychiatric) point of view, it is not hard to understand why earthworks and construction work arouse conceptualist artists' creative activities, especially if this work is being undertaken near the place they live. (It goes without saying that this connection is only relevant and interesting for those artists whose demonstrative sign fields are "transparent" in relation to the expositional field). Pantikov, for an example, thought up the actions "The Representation of the Rhombus", "Gunshot", and "Boots" when they were tearing up his entire backyard in order to lay some kind of piping under his house. (Usually, in our country, this kind of work continues for more than a year).

There are also more distant, mediated connections between the conceptualist and his "inspirator", (although here, admittedly, we are already departing in an much broader form of schizoanalysis). When I told Vladimir Sorokin about my conception of inspirators not too long ago, he remembered that he began to write his texts around the same time that they began to build his cooperative in Yasenevo. Actually, his house is part of a complex of three apartment houses (built in the form of three parallel semi-circles), a school, and a department store. Taken as a whole, they look like the four letters "CCCP" from above, as an acquaintance recently told him. One might also consider the connection between the incredibly long construction period of one single fundament of the Darwin Museum (which lasted for more than ten years) and the conceptual work of N. Alexeev and M. Roshal', whose house is located near this construction site.

However, there is yet another level of mediated connection between "inspirator"-systems. Take, for an example, the "objectifying" cultural and existential relations of Soviet and Western conceptualists with their respective "transparent" demonstrative fields. (In a sense, I am speaking of nothing other the obvious "screwing together" of one culture with another, which I wrote about in the essay "With a Sprocket in the Head".) In the course of this encounter, the objectivity of the expositional sign field reveals itself (and can be considered in the genre of critical confabulation) as the resultative context of several demonstrative fields. Of course, this can only happen if the reader is well-acquainted with the artworks in question. This objectivity actually manifests itself in "Earthworks", the autonomous conceptual artwork that we propose below in the form of photographic excursion from the VDKh-exhibition complex to Turgenev Square. On the other hand, all of these underpasses, above-ground sanitary constructions, trestles etc. can be simply considered as distinct points of interest in Moscow's landscape (and not as significant conceptual aspect angles), which I love to walk around, sights that Sabine and I recently strolled past on a late December evening.

January 1987

* * *

The series of photographs that follows this text depicts various "sacral" inspirators connected by one unified theme, which could be called "The Theme of the Peacock and the Condor on the Expositional Sign Field of Moscow". Once again, I would like to note that the plot of this photo-sequence is based upon the resultative context of the following fragments and artworks:

The 76th chapter of Wu Chen-en's novel "Journey to the West" (the episode on Buddha, the peacock and the condor-shapeshifter: the pavilions of the VDNKh All Union Exhibition of the Achievements of the People's Economy are the "Soviet peacock", while the condor is Kabakov's inspirator on Turgenev Square in the form of the "condor" building).

The performances of "Collective Actions"

The work of V. Sorokin ("The Path of Shit" – a photograph of an above-ground cesspool (?))

I TsZIN (The metro-station "Shcherbakovskaya", whose rotunda is located in the "Earth" trigram, formed by six apartment houses).

V. Yankilevsky's piece "Apartment #48"

The work of I. Kabakov

The unusual life and photographic adventures of A.M. and S.H. in Moscow and the Ruhr in 1984-1986

---------------

List of Photographs

0–000 Three epigraphic photographs of earthworks and construction operations.

1. Cesspool (?) across from the VDKNKh exhibition's Southern gate.

2. Cesspool (?) at the end of Ulitsa Tsandera

3. Apartment house on the corner of Ul. Tsandera and Ul. Kondratyuka. The "inspirator" for Collective Actions' chamber performances.

4. The place near the "Kosmos" movie theater (at the beginning of Ulitsa Kondratyuka), where CA's "inspirator" was located 1976-1980

5. "Shcherbakovskaya" metro-station (now "Alexeevskaya")

6. The underpass on Ul. Lobacheka (formerly "Proezzhaya"; I lived here roughly from 1956 to 1960).

7. Exit from the underpass on Ul. Lobacheka

8. Cement mixer (?) on the construction site between Ul. Lobacheka and Rusakovskaya Ul.

9. Flyover above Rusakovskaya Ul.

10. Under the flyover

11. View from Rusakovskaya Ul. onto Three Stations Square and Kirov Prospect (now Sakharov Prospect), which leads to the "Russia House", which houses Kabakov's studio

12. The "Condor" building on Turgenev Square (Kabakov's "inspirator")

13. View onto the "Condor" building from Sretensky Boulevard

14. View onto the "Condor" building from Kabakov's studio

15. Building of some other secret government agency (probably military) on Turgenev Square near the "Condor" building

March 15th, 1987

(In collaboration with E. Elagina)

А. Monastyrski

[1] Trans. note: In the English original, the last line of this famous passage from "Alice in Wonderland" reads "How doth the little crocodile...". The translation of this famously absurd variation on a children's rhyme into Russian has been solved in a number of ways. One of the most inventive translations is the one that the author cites here, namely that of N. Demurova and D. Orlovskaya, which alludes to a famous Russian children's rhyme.

[2] Trans. note: The author uses the term sushchee, which is best translated by the German Wesen (as opposed to Sein). The English analogy (essence vs. existence) is not very precise, but is used here, in correspondance with the tradition of philosophical translations.

[3] Trans. note: The author uses the Russian predmetnost' , which could be best translated by the term Gegenständlichkeit. This is not exactly the same thing as the English objectivity, which connotes a certain objective relation to the objects, rather than the tangible quality of the objects themselves. Objectivity is used here in lieu of Gegenständlichkeit, for the lack of a better word. It corresponds to the usage of objectivity in translations of German idealist philosophy.

[4] Trans. note: It is significant that the author uses the word perestroika (=rebuilding, reorganization, reconstruction) here, creating a contingent interpretational link to the text's historical context.

[5] Trans. note: Here, the author uses the Russian term bezobrazie, which connotes ugliness, nuiscance, or outrage, but literally means imagelessness (bez-: without; obrazie: image-quality). In this sense, deformity may be considered as the most adequate translation.

[6] The "Russia House" (Dom Rossija) is one of Moscow's most famous apartment buildings from the turn of the century. It was built by the Rossija-insurance agency. Kabakov had his studio in a loft here.

[7] Trans. note: The Hutsul are a small ethnic minority that lives in the Carpathian mountains of Ukraine and Romania. They speak a dialect of Ukrainian, but have many Romanian influences in their language, dress, and customs.

[8] Trans. not: A ZhEK (zhilishchno-ekspluatatsionnaya kontora) is the local housing authority responsible for a block of flats. Aside from communal maintainance, its competencies also include cultural and ideological affairs.

[9] Trans. note: Monastyrsky is refering to the installation "16 Ropes" (1983-5), where Kabakov collected deritrus from

[10] Trans. note: Monastyrsky is refering to two members of the "Collective Actions" group. Sergei Romashko is a Moscow philologist and translator, while Sabine Hänsgen is an expert for slavonic studies and film from Germany.

translated by Yelena Kalinsky